My experience with social media mirrors that of many people my age, shaped by the rapid evolution of digital spaces that emerged as I came of age. I joined Instagram in 2012, when I was starting seventh grade, during a time when the platform still felt experimental and unmoderated. Social media then was a frontier of self-expression. I wish now that there had been clearer boundaries or that my parents had understood how deeply these platforms would shape our understanding of connection, popularity, and self-worth.

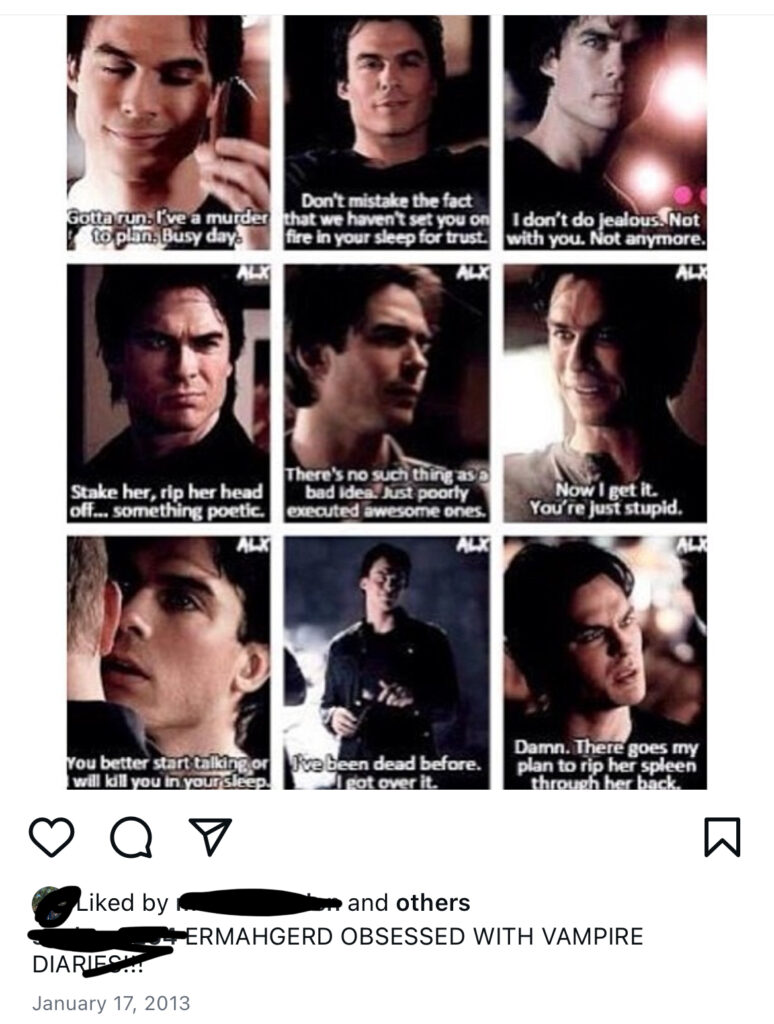

In those early years, I posted constantly. My feed was filled with selfies edited to extremes, captions stuffed with hashtags, and photos framed by heavy vignettes. I made and shared Vampire Diaries “memes,” though we did not call them that yet, and sometimes posted thirty in a single day.

I was endlessly entertained by my own creations. That changed suddenly in eighth grade, when a classmate casually mentioned that my constant posting was annoying. It was a small comment, but at the time it felt humiliating. That afternoon, I archived my account and started a new one. I can still access the old one, a digital time capsule of 761 posts. Looking back, that moment marked the beginning of my awareness that online spaces are not neutral. They are social environments, shaped by the same power dynamics, hierarchies, and vulnerabilities as real life. It’s fun and silly to have the digital capsule and I’m glad I have a clear snapshot of what was going through my preteen brain, but I’m also so embarrassed I ever posted so much of it to begin with!

My parents, like many at the time, had strong opinions about online safety but uneven digital literacy themselves. Facebook was off-limits because it was “too adult,” and YouTube was treated as dangerous, yet I had unrestricted access to Instagram, Pinterest, and Kik. It is almost endearing to recall how easily I blurred fantasy and reality. At one point, I became absolutely convinced that Harry Styles had personally messaged me through Pinterest and invited me to his concert in Toronto. I told all my friends we would have fallen in love if only my mother had let me go. That memory makes me laugh now, but it also reminds me how ill-equipped many young people were to navigate online spaces critically. We lacked the tools to discern authenticity, evaluate credibility, or recognize the constructed nature of digital content.

As I grew older, my relationship with social media became more strategic. I learned the unspoken rules of “coolness.” and what governed what acceptable media usage: post rarely, make it look effortless, and above all, appear curated but authentic. Slowly, my private life and my online life drifted further apart. What I shared became a curated snapshot rather than an honest reflection. My digital persona became more about how I wanted to be perceived than who I actually was.

In 2019, I began working for a small local shop and was responsible for managing their social media. This experience reframed my understanding of these platforms. I learned how to post consistently, design cohesive visuals, and engage with an audience in ways that built community. I discovered how social media could be used not only for self-promotion but for storytelling and advocacy. That position led to a similar role managing social media for the Indigenous Studies program at the University of Victoria during my undergraduate degree. I covered events, created newsletters, and highlighted student and community achievements. Around the same time, I worked as an assistant to a realtor, managing his listings and digital marketing. Through these experiences, I came to see social media as a professional tool, one that can amplify voices and create meaningful visibility when used thoughtfully.

Today, I find myself in a more complicated relationship with social media. I no longer manage it for others, and I use it less actively for myself, though I still spend more time observing than I would like to admit. Since deciding to become a teacher, I have become more conscious of how I am perceived online. In education, public image carries real professional consequences. Digital literacy for educators extends beyond knowing how to use technology; it involves understanding privacy, ethics, and the ways online behavior can shape credibility and trust.

Outside of teaching, I love to cook and host large dinner gatherings when I am home, sometimes for fifteen or more people. I often see creators online documenting similar experiences beautifully, transforming ordinary evenings into visual narratives. A part of me is drawn to share my own gatherings that way, but another part hesitates. I think my early experiences online taught me both the power and the precarity of visibility. I have worked really hard to reach this point in my professional journey, and I want to protect that. For now, I am content to let some moments exist offline. Perhaps that is my most valuable lesson in digital literacy so far: knowing when to engage with the digital world, and when to be in the real one.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.